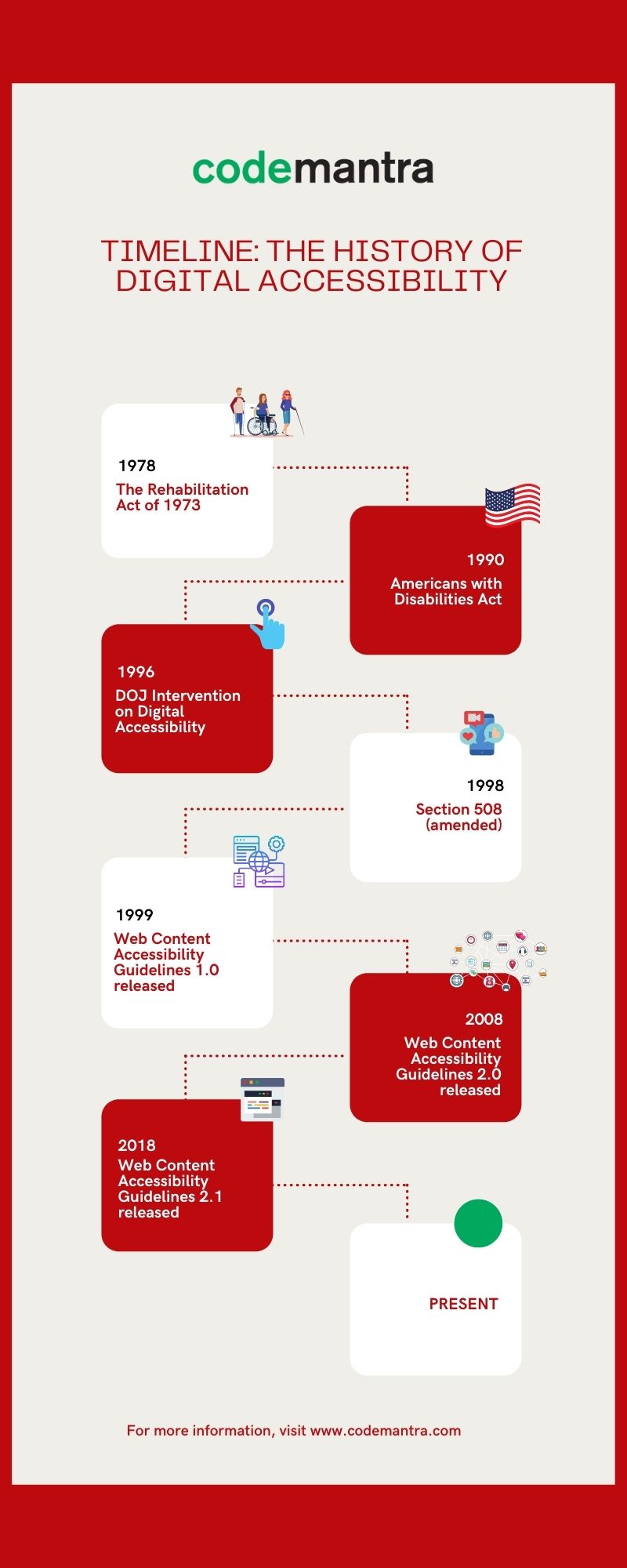

We live in a world of technology where the blind can overcome great physical feats and the deaf can “hear” music. It makes you wonder how we actually got here? One thing is for sure, we haven’t gotten to this point by accident; we are here by purposeful design.

What did it take to get here? Many battles, many policies, and a lot of people who care. And, yes, we still have a long way to go. This National Disability Employment Awareness Month (NDEAM), let’s dive into the past and walk along the circuitous and rocky road of digital accessibility that has led us to today. We’ll start with the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Many things come to mind when you think of the 1970s: bell-bottoms, seriously groovy mustaches, and possibly revival music. What you may not know, however, is that a critical law passed in 1973 had a very positive impact on millions of people with disabilities: the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This act prohibits federal agencies (and their contractors) from discriminating against individuals on the basis of a disability, whether it be through employment, financial assistance, and last, and by no means least, technology. This means that any type of technology (from official documents to websites, apps and more) deployed by the federal government and its contractors needs to be accessible to people with disabilities.

Americans with Disabilities Act (1990)

Most people have heard of the Americans with Disabilities Act, or the ADA, as it’s often referred to. However, it’s more common for individuals to think of it in relation to accessing a physical space. For example, a wheelchair ramp, or large bathroom stalls with rails.

However, the ADA is a very interesting case study in itself. This is primarily because when it was passed in 1990, the Internet was a nascent initiative and few people (with, perhaps the exception of its inventor, Tim Berners-Lee) ever considered how it might need to be interpreted for digital content. However, today, multiple judges have ruled that websites, apps, and the like are considered “places of public accommodation,” and need to be accessible to people with disabilities. With each passing year, the government is increasing mandates for agencies and other institutions on accessibility. As of February 2020, the DOJ entered 175 settlement agreements that address web accessibility.

DOJ’s Stand on Digital Accessibility (1996)

Once internet use began to spread like wildfire, people with disabilities were understandably frustrated when they couldn’t access the content on the web. But because Title III of the ADA (the section that includes the reference to public accommodations) didn’t specifically identify digital content as “public,” they had no legal recourse. That is, until the DOJ publicly asserted that, yes, websites are considered public accommodations.

As of February 2020, DOJ entered into 175 settlement agreements addressing ICT accessibility. However, given that DOJ does not offer clarification on digital content, it’s up to the courts to decide on accessibility rights. In a recent supreme court ruling involving Domino’s Pizza, the supreme court denied a petition from the F&B major. Domino’s Pizza fought their lawsuit tooth and nail, even sending a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court for appeal in summer of 2019. However, the Supreme Court rejected their petition, and Domino’s Pizza will now be facing a very public trial – essentially fighting to have the right to discriminate against blind people. Tough luck, Pizza anyone?

Section 508 amended (1998)

When the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was made into law, technology wasn’t quite where it is today. Even in 1986, when the Section 508 amendment was added to expand the Act’s purview to those working as contractors for the federal government, the internet as we know it today was still a decade away. That’s why the year 1998 is so critical to digital accessibility: it’s the year Section 508 was amended to include digital content. For all intents and purposes, the Section 508 amendment means that both the Federal government and organizations that want to do business with the federal government both need to have accessible digital assets. So, it would be folly to think that that because this only applies to the government.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 released (1999)

Tim Berners-Lee, the “official” founder of the internet was quite keen on ensuring everyone had equal access to it. Berners-Lee and the web guidelines group he founded, the W3C, first came out with WCAG 1.0 in 1999. The 11 page document comprised 14 guidelines that each covered a specific element of web accessibility and “65 checkpoints”. The guidelines included accessibility touchpoints like: Equivalent alternatives to auditory and visual content and providing clear navigation mechanism for people with disabilities. WCAG 1.0 was a landmark step towards making the web a more inclusive place. The hard part was encouraging organizations to embrace it.

WCAG 2.0 released (2008)

After almost a decade of the release of original Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, the W3C came out with an updated version, WCAG 2.0. Seeing as how the original guidelines were created in a time when Netscape was still the gateway to the web for most people and email was still a “future technology,” the update was eagerly embraced. The second version of the guidelines built upon the foundation created by its successor and focused on four distinct principles: Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust. Included with these principles were more guidelines for developers to ensure an accessible web experience for all users.

WCAG 2.1 released (2018)

Almost on schedule, ten years after WCAG 2.0 was introduced, the indefatigable W3C released WCAG 2.1. This is the current version of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, and is what organizations striving for accessibility should aim to conform to. The main difference between WCAG 2.0 and 2.1 is an emphasis on underrepresented or absent elements in WCAG 2.0. For example, the new guidelines included more information on accommodating those with cognitive disabilities, who use speech input software, and who leverage screen magnification features, to name a few.

Final Thoughts

The fact is that the need for digital accessibility is not going away, and nor should it. In America, studies estimate that over 26% of the population lives with a disability. This number will undoubtedly grow as the years progress. It’s also important to keep in mind that each of us are growing more disabled every day, simply by growing older.

Smart agencies know to read the writing on the wall and to embrace future trends far before they become mainstream. As digital lawsuits continue to increase exponentially, now is the time for forward-thinking leaders to conduct an assessment of their digital assets and ask themselves if they want to be leading the charge to the future or scrambling to catch up.

Don’t get left behind! Schedule a Demo and try codemantra’s award-winning accessibility platform today.

- Charting Your Accessibility Journey in the State of Illinois - December 6, 2021

- Demystifying Document Accessibility: 10 Tips to Help Get you Started - November 3, 2021

- Looking Back at Digital Accessibility and Its Significance Today: Timeline of Consequential Events - October 21, 2021